Integrated Gradients

Published:

Update (7/02): I’ve mostly finished this post now, we’ll leave it here.

My favorite part of every whodunnit movie is the final scene when the detective breaks down how the perpetrator committed the crime, and we see a montage of previous film scenes highlighting the clues we, the audience, presumably missed. To put it in internet parlance, The Summation Trope.

Deep networks don’t tie everything in a bow as nicely as Agatha Christie does. We may be able to train a network on Sherlock Holmes novels to spit out the murderer, but, even when they get the answer right, they’re still not great at explaining how it all happened.

This is frustrating as a would-be mystery solver, but it’s also potentially dangerous. As more and more decisions about things like who gets a loan and who gets bail we can notice anecdotally and statistically that they are as, if not more, prone to bias as human decision makers. Yet controlling and correcting these biases eludes policymakers and technologists, in part because of the black-box nature of their implementations.

Attribution and saliency methods are among tools that purport to offer the mystery “wrap up” for a deep network. By pointing to what aspects of the input they used or focused on in determining a model’s output, they offer some way to assign “blame” for particular behaviors on aspects of the model.

In this post I’ll talk briefly about why this is hard and go through details of one such method, the integrated gradient described in Sundarajan et al., 2017. My exposition here is also influenced by two blog posts – from Sundararajan, Taly, and Yan (2017) and Chalasani (2018). My goal is to express the technical details in laymen’s terms in order to motivate a brief discussion at the end of this post on some of the differences between what attribution methods can do vs. what they purport to do. While I’ll hopefully return to that topic in a later post, if you’re particularly interested I suggest reading this extremely approachable blog post (Jacovi, 2019) which was later expanded into this also approachable paper (Jacovi and Goldberg, 2020). Anyway, let’s get into it…

Integrated Gradients

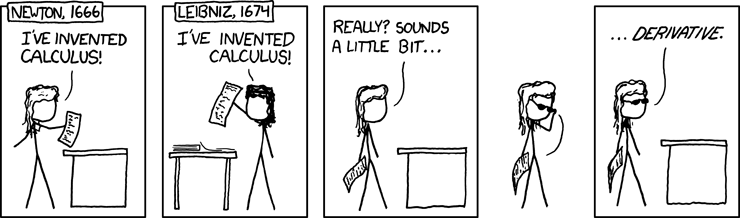

|  | |:–:| | That whole whodunnit trope can feel a bit derivative, and so can some of the technical tools we’ll be using. 😉. |

| |:–:| | That whole whodunnit trope can feel a bit derivative, and so can some of the technical tools we’ll be using. 😉. |

Some quick notation

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| $F : \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow [0, 1]$ | deep network |

| $x = (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n) \in \mathbb{R}^n$ | input |

| $x’ \in \mathbb{R}^n$ | baseline input |

| $A_F(x,x’) = (a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n) \in \mathbb{R}^n$ | attribution of the prediction |

| $a_i$ | contribution of $x_i$ to the prediction $F(x)$ |

Attribution in a linear model

Suppose we have a simple linear model, $f = ax_1 +bx_2 + c$. Then, if $a > b$ we can make a reasonable argument that $x_1$ is more important than $x_2$ in building our prediction. Say we’re trying to predict the weather for today and $x_1$ is today’s weather report and $x_2$ is what color shirt I’m wearing today, we’d expect $a » b$. If that weren’t the case, we could use that information to go back and investigate what went wrong with our model – overfitting, bias in the training data, correlated variables (maybe I only wear blue shirts on days when I’ve read the weather report and determined that it’s going to rain).

Another way to look at the coefficients $a$ and $b$ is that they are derivatives or, gradients. This is helpful, because while we don’t have access to coefficients in a deep network the same way we do in a linear model, we can approximate something close to a gradient.

Baseline as scientific method

Without diving too deeply into Wittgenstein, I want to simply assert that humans perform attribution by counterfactual intuition. If we want to blame the outcome $y$ on $x$, then we need to consider if $x$ hadn’t happened, would $y$ have happened? The scenario where $y$ didn’t happen is our baseline, or control, which we define as $x’$. In other words, to firmly demonstrate that the murder was committed by Miss Scarlett in the Billiard Room with the Candlestick, I need to establish that had Miss Scarlett not been in the Billiard Room with the Candlestick, the murder – as I see it – would not have happened. For more formal approaches to justifying the need for a baseline, see Shrikumar et al., 2016 and Binder et al., 2016.

What should we use as our baseline? Ideally we would use a zero vector. In an image task this makes sense, we use a “blank” image. It’s a bit more difficult to decide what to use as our baseline “neutral” for a text task, though many implementations use a neutral word like “a” or “the” repeated to match the length of the target input $x$.

Axioms

What made the coefficients above a good tool for identifying feature importance? There’s no clear correct answer for what a network’s attribution should be, rather we can only assess a particular attribution method based on whether it feels “reasonable.” Above, we chose to interpret magnitude as importance, and this made sense given both what we expected to see and they way we understand our own, human, approach to interpretation. That said, we can try to formalize some of the desirable properties of an attribution method.

Sensitivity

Formally: If an input and a baseline differ in exactly one feature but have different predictions, then the differing feature should be given non-zero attribution.

Informally: If two games of Clue are exactly the same except for the order of two cards in the deck, then the attribution for who wins the game should be placed on those two cards.

Insensitivity / Sensitivity (b)

Formally: If network does not depend at all on the value of a particular feature, then attribution to that feature should always be zero.

Informally: If taking a card out of the game of Clue never changes the game, then the blame for a particular game outcome should never be placed on that card.

Implementation Invariance

Formally: Two deep networks are functionally equivalent if their outputs are equal for all inputs, regardless of how they were implemented. If two deep networks are functionally equivalent, the attributions should always be identically.

Informally: If two games of Clue are exactly the same just one is in Spanish, the attributions should be the same (I should probably tighten this analogy a bit).

Completeness

Formally: The attributions of $x$ should add up to the difference between the output of $F$ at $x$ and the output of $F$ at the baseline $x’$.

Informally: The bad news is, I’ve lost the analogy. The good news is, it was probably making things more confusing anyway.

Linearity

Formally: Suppose that we linearly composed two deep networks, $F_1$ and $F_2$ to form a new network $G = a * F_1 + b * F_2$ then any attribution method should preserve linearity on the new network. So the attribution, $a_g$, of $x$ to $g(x)$ should follow $a_G = aa_{F_1} + ba_{F_2}$. Yikes, I should have chosen better notation or at least not be lazy with my TeX. Oh well, no one’s reading this anyway.

Symmetry-Preserving

Formally: Two input variables are symmetric with respect to a function if swapping them doesn’t change the function. If two variables play the exact same role in the network – they are symmetric ($F(x_1, x_2) = F(x_2, x_1)$) and have identical values in the baseline and in the input ($x_1 = x_2$ and $x_1’ = x_2’$) – then they ought to receive the same attribution – $a_1 = a_2$. An attribution method is symmetry preserving, if for all inputs that have identical values for symmetric variables and baselines that have identical values for symmetric variables, the symmetric variables receive identical attributions.

Path methods

It turns out that not a lot of attribution methods satisfy all of the properties above. For instance, basic gradients on their own don’t satisfy this sensitivity (a) requirement. This is because gradients are local.

Beyond that, path methods satisfy some of these requirements, but the only path method that satisfies all of them – namely completeness (which implies sensitivity) – and that’s integrated gradients!

Integrated Gradients

I am, TBH, losing steam. I started writing this post Day 1 of WFH, it is now Day… idk, but Month 5! Can you believe it? I sure can’t.

I’ll assume the reader knows what a gradient is. The integrated gradient along the $i^{\mathrm{th}}$ dimension for an input $x$ and baseline is defined as:

We can approximate this by summing the gradients at points occurring at small intervals along the straightline path from the baseline $x’$ to the input $x$. Given $m$ as the number of steps in the approximation of the integral, we have:

Applying integrated gradients

The equation above translates pretty easily into code.

I did this, I promise I did this. I did it while pair-programming with fellow scholar Kata. It was a joy. I had witty examples I was going to put here. However, the two blogs linked above also have brilliant examples that are extremely clear. Maybe I’ll update this in a bit. Maybe I’ll take this whole blog down in a week.

Language models and integrated gradients

The problem is sufficiently harder outside the image space. Here are a couple of reasons for this:

- It’s hard to identify a good baseline! In the image space we can use negative space as a reasonable approximation of 0, it’s less clear what words apply to 0. Most techniques use something like

the the thewhich works but has issues. - Text undergoes multiple transformations in transformer models (go figure), from sentence to embeddings to attention. Whereas image attribution methods can highlight attention as pixels, it’s less clear what to attribute to for text to get both faithful attribution metrics and readable results.

Integrated gradients and policy

There is clear demand by the regulatory community for better understanding of how deep learning models work. While GDPR does not explicitly outline a “right to explanation,” it does require that subjects of a decision-making algorithm have a right to “meaningful information about the logic involved” in reaching that decision. The recent European Commission White Paper on Artificial Intelligence states a commitment to European leadership on developing new AI algorithms and specifically tools to “help us improve explainability of AI outcomes.” As an example of how policymakers are putting this into practice, in 2019, HUD proposed a rule to undermine the Fair Housing Act in part arguing that requiring companies to explain disparate outcomes of algorithmic models would hinder the efficacy of those models.

Simultaneously, there is disagreement in the ML community on the gap between what interpretability tools like integrated gradients purport to do and what they actually measure, as well as a lack of clear definitions for terms like “interpretability” and “explainability.” Jacovi and Goldberg (2020) provide a clear and concise overview of the field and how to standardize definitions, but don’t make an effort to bridge the gap between precise technical definitions and their use in the policy community.

The debate stems from a few places:

- Explainability and interpretability are used interchangeably, when some people intend them to mean very different things.

- It’s unclear how much human values of explanation translate to machines, and whether different methods are just putting a square peg of “how we understand human decision-making” into a round hole of “how deep learning models actually work.”